In his tribute to the art of reading, the author and former Director of the National Library of Argentina, Alberto Manguel, declares, ‘We are what we read’. He does so in response to Walt Whitman’s assertion that the process of reading is merely an intellectual one. Manguel contends that unconsciously, the reader and text become intertwined.

Researchers at the Washington University Dynamic Cognition Laboratory in St Louis, Missouri, would concur with Manguel. They found that deep reading creates a sort of virtual reality, as the reader constructs a mental simulation of the narrative as they read. For example, if a character in the book someone is reading pulls a light cord, activity in the reader’s brain increases in the frontal lobe region which controls grasping motions.

In essence therefore, the reader becomes the book.

‘Deep’ (or slow) reading is, I assume, a more meditative activity than say, rapid reading. My blog post on How to remedy excessive daydreaming and get writing explores the latter, citing Geoffrey A. Dudley, B.A. on the benefits of ‘Rapid Reading’ (1964)

Dudley wrote several self-improvement books from the late 1950s to the mid ’90s, and while he never told us to go deep, he did tell us that in order to read faster, we must first learn to concentrate.

Concentration is surely required for all reading, fast or slow, is it not?

In ‘Jake the Dog’, a charming story by the author Norah C. James (whose first novel was banned in Britain in 1929), narrated from the dog’s point of view, we find Jake observing his owner, ‘holding a stiff, flat thing in front of her face and staring at it. It was a queer thing to do, he thought’.

In our attempt to concentrate, to eliminate distraction and sustain our attention upon that ‘stiff flat thing’, we must consciously remove ourselves to another place, generally a place of repose. We need to go, ‘off the grid’ as Will Schwalbe stipulates in, ‘Books for Living: a Reader’s Guide to Life’, (2016).We can’t interrupt books he says, we can only interrupt ourselves while reading them.

Doing just that and totally immersing ourselves in the act of reading may be more difficult for some. Leonard Lowe, who had contracted Encephalitis Lethargica (sleeping sickness) at the age of eleven in 1921, was an avid reader.

Leonard’s life history is featured in Oliver Sacks’ medical memoir, ‘Awakenings’ (1973). Speechless and without voluntary motion (except for minute movements of one hand), Leonard became the hospital librarian and composed monthly book reviews for the hospital magazine. In 1969, the neurologist Oliver Sacks administered a new ‘wonder drug’, L-DOPA (also known as levodopa and levodihydroxyphenylalanine), and as a consequence, Leonard’s reading became more difficult than ever – Sacks tells us how the drug’s adverse side effects compelled Leonard to read faster and faster, without regard for the sense or syntax. He would have to shut the book with a snap after each sentence or paragraph, so he could digest its sense before rushing ahead.

Leonard Lowe’s story is incredibly moving. Sacks writes that Leonard, along with his other patients, taught him what it means to be a human being who survives, and fully, in the face of such affliction and terrible odds. (Leonard is played by Robert De Niro in the 1990 movie, Awakenings.)

Miriam H., another patient treated by Sacks, had a strange intermittent compulsion to count, described as a form of arithmomania that signalled her need to order, disorder and reorder. She read omnivorously with great speed and intentness. Using her eidetic or photographic memory, Miriam could remember the exact number of words counted on every page. She could read AND count at the same time.

Sacks’ account is heart wrenching. The social scientist and bioethicist Tom Shakespeare once described Sacks as the man who mistook his patients for a literary career (echoing Sacks’ most famous title, ‘The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat’), but I’m grateful for the opportunity to learn from Sacks’ writing.

I’m often reminded at book club sessions that our encounters with books and our simulated realities are altogether unique. I enjoy the Louth U3A Reading Group sessions, and I’m grateful to Amanda Watts who organises and facilitates the new Louth Book Club which meets at The Priory. At these convivial sessions we acknowledge our different perspectives by agreeing to disagree and we come away enriched by the communal act of reflection.

David Ulin in, ‘The Lost Art of Reading: WHY BOOKS MATTER IN A DISTRACTED TIME’ (2010), tells us that as ‘deep’ readers, we’re asked to ‘slip inside’ a text. Ulin contrasts deep or meditative reading with, for example, our propensity these days to skim the surface of each subject as we fail to concentrate, to pursue a line of thought or tolerate a conflicting point of view (whatever that view may be – another topic for another day).

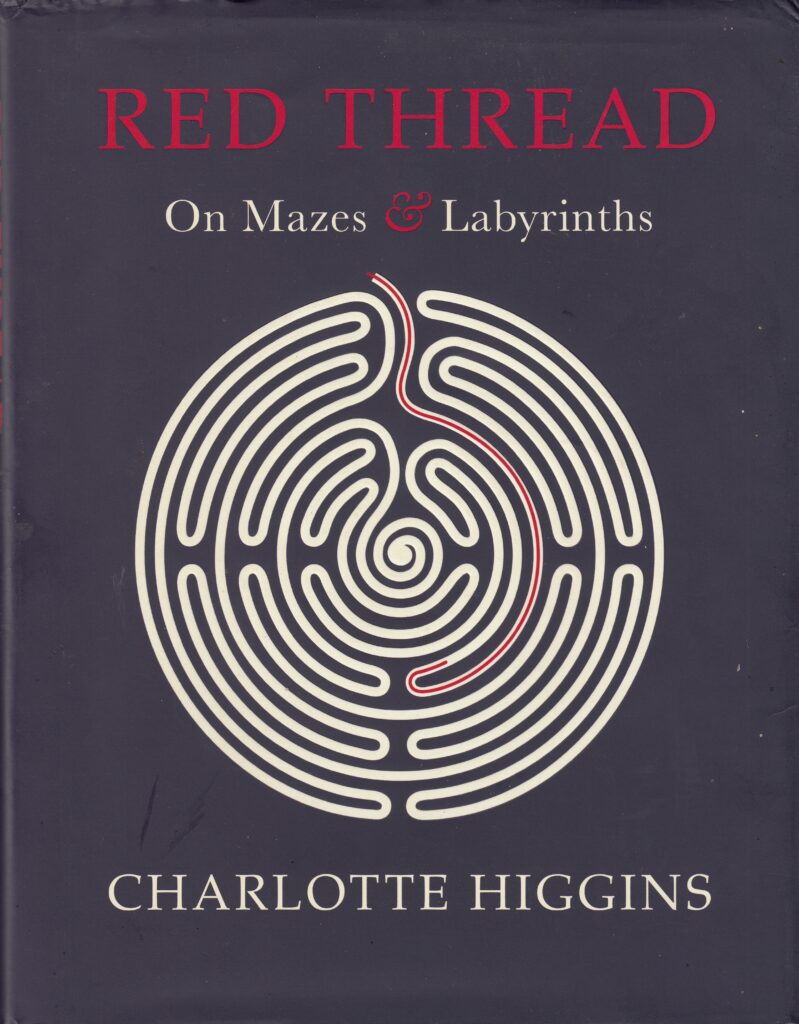

Books and labyrinths

Reading a book is never a passive experience – for any of us – and the same may be said for threading a labyrinth, however we may choose to engage with it. A labyrinth may be encountered in many different ways; contemplated, traced, drawn, painted, carved, planted, sewn, worn, walked, and danced. And our experience is often transformative.

Charlotte Higgins, in her intriguing exploration of the idea of the labyrinth, ‘Red Thread: On Mazes & Labyrinths’ (2018), tells that on entering a labyrinth, humans, ‘spin thread, they tell stories, they build structures … there is meaning to be made, meaning to be excavated.’

Like reading, the labyrinth experience and the meaning it creates is different for every person. I’m reminded of Dr Margaret Rainbird who took a year-long “Labyrinths for Life” world tour in 2017 and describes labyrinths as being a bit like people. She says,

“There are some that I feel an immediate emotional connection with and others where there is no chemistry at all.”

Higgins refers to writers of the Middle Ages who speculated upon the etymology for the Latin for labyrinth, connecting the word, ‘laborintus’ with the phrase, ‘labor intus’, meaning ‘labour inside’. She says the labyrinth became a proxy for the labour of life, ‘the work of knowing the self; and the struggle to read the labyrinth of the world.’

Higgins also quotes her recent correspondence with a Mrs Sofia Grammatiki, who had many years earlier guided Higgins and her parents around the museum at Heraklion, near Knossos on the island of Crete during a family holiday. Mrs Grammatiki views the labyrinth as a symbol of the imagination, representing the manner in which humans make associations. She says that stories have this comfort in them; they have a beginning and an end. They find a way out of the labyrinth.

(I wonder if Mrs Grammatiki ever read Italo Calvino’s labyrinthine tale, ‘If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller’ (1980), and if so, what she made of it. I suspect she’d give it the thumbs down, like most of my book club friends. Personally, I loved it.)

Having reflected on the comfort of books and things in my post on Finding Comfort in Still Life last year, I can see what Mrs Grammatiki is getting at, although I do appreciate that reading may at times be uncomfortable. And that is not a bad thing. It does us good to be challenged, as I found recently with David Jarrett’s profound memoir, ’33 Meditations on Death: Notes from the Wrong end of Medicine’ (2021). While the book is life affirming in many ways, I did find his unflinching chapter on, ‘Dying á la Mode’ brutal and tender in equal measures.