Guy took up the pitchfork, turned over the steaming layers, closed his eyes and inhaled the rich aroma of decay. This had to be as good as taking a drag. He was remembering the bitter taste of a cool, slow burning cigarro. In an instant, his emotional receptors were in full throttle as he found himself back in the old life, passing out the Dominican classics to mark the new-born’s safe arrival. Standing outside the birthing station all those years ago, he knew just how privileged he had been and had wanted to share his joy with the other appointed fathers in the time honoured way. The burden of his daily toil servicing the Heap failed to supress the sweet intoxication of this wistful memory. Happily, the genetic lineage of Guy J. Liberus had been deemed worthy and was assured, for at least one more generation. He hoped his offspring, now fully grown, had inherited above all, his strength of character, as the love of books, though no doubt hard-wired into their brain, would be futile.

The past would often come flooding back, although the memories were not always joyous, and Guy would have to stop himself from sinking into self-pity by concentrating on the job in hand; those crates were never going to sort themselves. His main task, after all, was to select only those books fit for biotic processing, those unsuitable being discarded and destroyed.

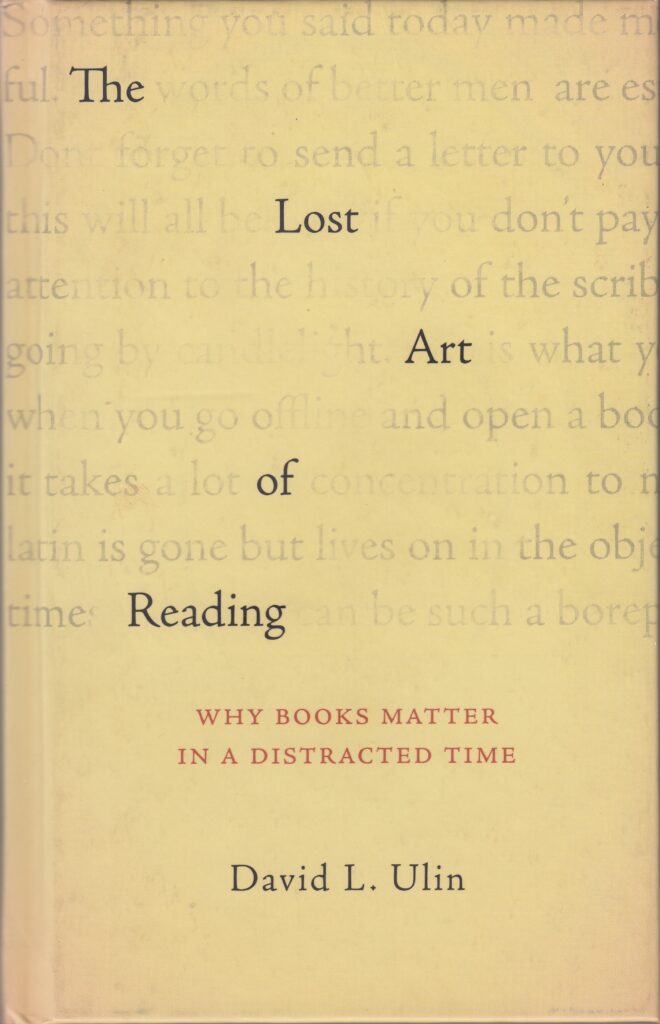

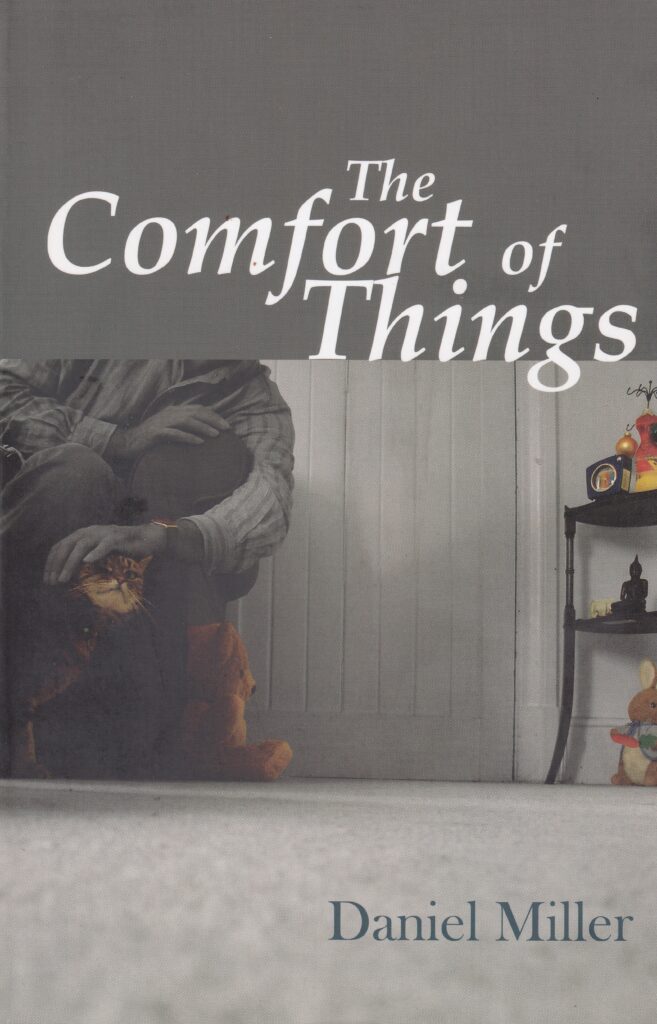

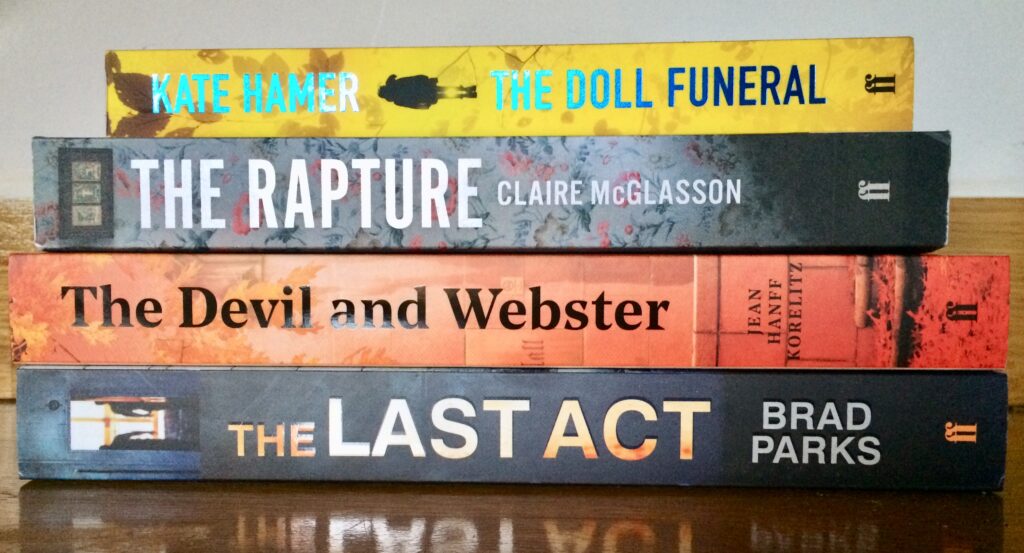

As a man of letters, he could never resist thumbing through each copy before deciding its fate. He picked up a mid-twentieth century edition of ‘Remembrance of Things Past’ and gave a sardonic smile as his own Proustian memory, his ‘Madeleine’ moment, came to mind. He took another imaginary drag. Ah oui, Monsieur Proust, smell is undeniably remembered as a feeling. It was hardly surprising that Guy had become addicted to the fragrance of old books. Their aromatic undertones, generated by the breakdown of organic compounds; benzaldehyde, with its almond-like scent, vanillin and ethyl benzene, were a source of great comfort. This two hundred year old volume he held tenderly in his hands, imparted the scent of its own degradation and reeked of a lost age.

Old editions with untreated paper were the best. The Proust was ideal, and although sorely tempted by the prospect of re-reading this seminal work in its original form, Guy knew he would never get away with sneaking all seven volumes of such high grade material past the smart sensors. He reluctantly placed them into the treatment bin and thought about their last owner who had probably, like so many, begrudgingly ‘donated’ their exquisite literary treasures to the cause.

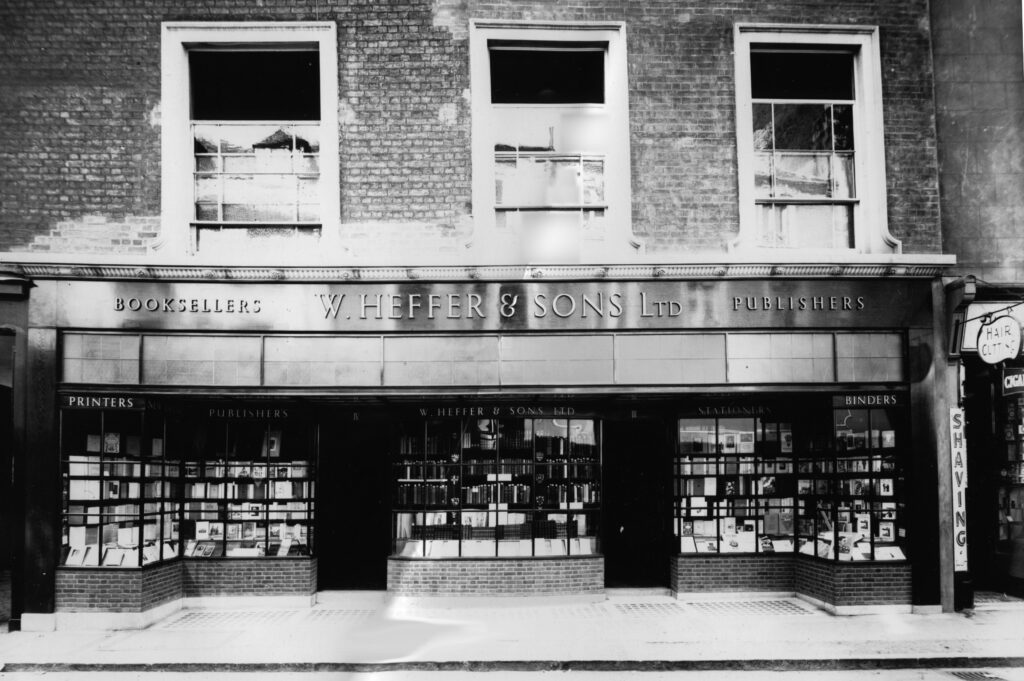

Guy still had his own private scholarly collection at home, meticulously gathered over decades of prolific reading; an intellectual realm that mapped the chronicle of his long life and mirrored his insatiable thirst for knowledge. Not only did he read extensively, he also liked to own every book he read and found it almost impossible to let any go, even those that failed to satisfy. There were times when this attachment could be seen as bordering on the ridiculous, though never by his own well-read tribe who, over several generations, included renowned booksellers, bibliophiles and free spirits. His grandfather and namesake loved to share stories about his bookish adventures; that time on a family holiday, across the Irish Sea in Galway when, aged nine, he had been accidentally locked in a bookshop at the close of business; that awkward moment a few years later when he told the proud university librarian that the prized first edition they brought out to show him was in fact, a second. Books were Guy’s birthright. Naturally, he preferred their company to people.

Sometimes at the Heap, Guy was assigned to the dispiriting task of dismantling and layering the literary material selected for processing, and while doing so he would often flinch at the sight of books being de-fleshed. The best brown elements for aerobic digestion and composting were those that had started out their life as a tree. All bindings and glossy covers had to be removed, but the cardboard covers and pages could be retained as they would eventually break down. The porous nature of the remains enabled air to penetrate and excess moisture to escape. Mixing and turning the top layer on a regular basis accelerated the aeration, although it would still take several weeks for the decomposition to reach the thermophilic or sanitation phase, after which a series of secondary reactions cooled and cured this pungent lasagne into a friable humus suitable for spreading.

From time to time Guy reflected on how similar this process was to the stacking and fermenting of tobacco leaves that would turn from blonde to black and eventually sweat down to a mellow woody compound. In the late twentieth century, Guy’s ancestor Sidney had cultivated and cured his own pipe tobacco at home. He was rumoured to have used antifreeze as an additive, hopefully just propylene glycol, which would have given the do-it-yourself baccy a sweeter flavour. Nevertheless, the family did at the time strongly suspect the incorporation of the potentially toxic motor coolant conveniently stored in Sidney’s garden shed. Whatever the recipe, it seemed no harm was done as he lived to a ripe old age.

Within sixty years of Sidney’s passing, as the Earth’s surface temperature began to rise at an alarming rate, curing tobacco on a domestic and industrial scale, along with many more damaging enterprises, had been superseded by a profusion of heat mitigation projects. Record breaking heat waves and droughts, fanned by heat domes, El Niño and the persistent burning of fossil fuels, had lengthened the natural fire seasons. Those greenhouse gases that had for ten thousand years kept the planet at a reasonably comfortable temperature for human habitation, were trapping more and more of the Sun’s harmful rays.

Instead of cooling their tobacco, the tabaqueros, through sheer necessity, joined collective efforts across all nations to cool a bruised Earth, rendered black and blue by countless wildfires and floods. Reforestation was the way forward. Greening on a small scale had already been well established, mostly through the worldwide Transition movement. Communities in villages, towns and cities had understood the need for the restoration of landscapes and ecosystems and had come together to build a low-carbon future. Guy’s grandfather, despite being a young US-based tech entrepreneur in agricultural intelligence who tracked commercial crop yields around the world, earnestly joined the American Community Garden Association and contributed to his local urban neighbourhood rewilding project in the mid-2020s. Public parks, school grounds, vacant and derelict land and even domestic gardens, were transformed as ‘going green’ became the mantra. The climate fightback was underway and Sidney’s vegetable patch and tobacco shed, swamped by boscage, was unrecognisable.

Millions of trees were planted in this global effort to reduce the number of heat-related deaths, and biodynamic agriculture became a by-word for a more diverse and resilient environment. Traditional land practices such as crop rotation, irrigation and heavy fertilizer use, conveniently disguised by ambitious tree planting schemes, continued for a few years as governments colluded with major producers to distract everyone from what was really going on. While the term ‘greenwashing’ had been coined in the late twentieth century, it was several decades before the crime of agronomic false greening on a global scale had been fully exposed by the Greta Thunberg Foundation. Only then was the practice of intensive farming abandoned.

As a responsible citizen, Guy had joined the Climate Majority Project, a movement that was still going strong since its inception over a hundred years earlier, in 2023. His great-grandmother, a social historian at the time, had once dabbled in non-violent direct action with the notorious Extinction Rebellion campaign, but despite having picketed with striking coal miners in North Yorkshire decades earlier as a young postgraduate student, her squeamishness for street blockades and sit-ins soon kicked in. She returned to her books and kept her head down.

Having inherited the ancestral aversion to civil disobedience, Guy belonged to the more mainstream movement in which he felt at home. In the spirit of supporting the climate-concerned majority, he dutifully went vegan. By then, quitting animal protein had become more of a financial necessity because of the tax levied on red and processed meat, although the practical benefit was the ten more years of life expectancy afforded by a plant-based diet. For Guy that would be ten more years to enjoy books, for he would never stop buying hold-in-your-hand-put-on-your-shelf books.

Until a shattering proclamation changed everything. Twenty years ago, that timeworn expression, ‘Stop the press!’ had taken on a darker meaning when every printing press in every nation had been decommissioned, and a decree made for the appropriation of all printed matter; books – hardbacks, paperbacks, and folios; newsprint – broadsheets, tabloids and gazettes; circulars – magazines, periodicals, journals, bulletins and reports. Initially, only public collections were seized and removed to classified treatment plants. Public libraries, large and small, were dismantled and could no longer serve their few remaining cardholders. Then, much to Guy’s dismay, the authorities began to acquire institutional and private collections through a system of enforced endowments. Academic library syndicates, urged by their affiliated librarians and scholars, rigorously defended their acquisitions to no avail, while spurious investors who had been collecting just for the money, readily gave up their rare editions in exchange for the prospect of an early place on the Great Exodus.

Some readers had always repurposed books, employing paper craft skills to transform the pages into envelopes, wrapping paper, confetti, wreaths, flowers and even chandeliers; stripping out the spines to make bookmarks, and turning entire books into sculptures, trinket boxes, journals and plant holders. Guy had engaged in none of the above. In his eyes, dismantling a book was tantamount to an act of self-harm, or possibly worse since the injury could never achieve even the slightest sense of release. More egregious, were the rippers who rendered a book worthless by visiting libraries and charity shops and surreptitiously tearing out single pages, before placing the vandalised volume back on the shelf. Suddenly, none of these irritations mattered and Guy found himself in a living hell.

The principle of leaving the planet better than you found it had been long established. While Scouts UK, with its many ideals, had withdrawn its pledge to the British monarchy long before the Sovereignty’s demise, it had remained true to the doctrine of sustainable living, and as a Boy Scout himself, Guy had had no argument with promising to do his best and to love the world. His father, a solar geoengineer with both eyes firmly on the Doomsday Clock, had devoted his life to securing the Earth’s future as a planet fit for human habitation by restoring the correct energy flows and therefore balancing the Earth’s ‘energy budget’. On the assumption that there was no time to waste, the man had worked on the award winning Becquerel Stratospheric Aerosol Injection Programme, which attempted to mitigate the temperature rises by spraying particles into the stratosphere that would reflect the sun’s energy away from the Earth, back to space.

While thankful that his old dad was no longer around to witness the annihilation of the world’s literary heritage, Guy was daunted by the prospect of butchering his family’s priceless collection alone. Destroying libraries was nothing new and as he prepared to face this gruesome task, he thought of a few notorious examples in historical times of conflict, when irreplaceable collections had been lost, not all as the result of enemy action. He had read that during the Second World War the English populace (Guy’s ancestors excepted) willingly handed over their books for recycling and reuse, in response to a national salvage campaign. Sixty million were destroyed although some were saved and later dispatched in peacetime to war-damaged libraries abroad.

By then the world was on the brink of the third industrial revolution, heading towards a new digital age that transformed the reading experience. The first prototype electronic reader appeared back in 1949 and ever since, doomsayers had wrongly predicted the death of the printed book, despite the more recent popularity of brain implants that not only enabled a reader to instantly download any text on demand, but also enhanced their ability to follow a story from beginning to end by blocking the compulsive urge to check their communication devices every few minutes.

Fortunately for Guy, this particular augmentation was never mandatory. Instead of submitting to these invasive technologies, he had always been free to enjoy the deliciously tactile sensation of sitting down to read on his own terms. The touch, feel and smell of a book; the act of turning the pages and unfolding the story; of annotating quotations and in a way, having your own private conversation with the author; the growing sense of achievement as you move through a book, changing the bookmark place; the sense of durability when there is no need to refresh the page; no distractions, no getting sucked into sponsor notifications that lead you down a rabbit hole; and no screen fatigue that would stop you from falling asleep at the end of the day.

Guy never was convinced by those who claimed that technology offered books a guaranteed immortality. While the storage issue had supposedly been resolved through high capacity cloud based petabyte-scale solutions, not all digital files were being updated, which rendered them inaccessible when systems were upgraded. The fact that his own library had been digitised along with everything else in preparation for the Great Exodus, was not reassuring, although he fully accepted that even with a photographic memory, it would take many lifetimes to memorize every volume. And anyway, a ‘remembered’ text would no doubt lose its precision with each shifting recollection.

He struggled to imagine this new existence, one without access to physical books, especially his books. They had been his greatest treasure and in recent months, his only company, with each book representing a small parcel of energy infused with a creative force that informed and vitalised his spirit. While remaining aware that he was physically holding a book, as he turned the pages he would find himself travelling to an inner realm of memories and imagination, where time past and time future merged with the present. Artificial intelligence with its deep brain simulation and synthesised imagination was an anathema, and Guy never felt more human than when he was reading.

Two years previously Guy had been put to work on his local branch of the Heap, located within easy reach of his modest quarters on the westside of his ancient university city which now, thanks to rising sea levels, rested on the shores of the resubmerged Fens, the erstwhile breadbasket of Britain. The university library, the college libraries and their individual academic collections had been dismantled after the public libraries had been cleared; eight million books in the university library alone, including a first edition of Newton’s ‘Principia’, Darwin’s personal copy of ‘On the Origin of Species’, and a copy of the Gutenberg Bible. The priceless volumes from these venerated institutions made for exceptionally rich material. Guy knew it was only a matter of time before he would become the grim reaper of his own, for it would be his job to sort his collection at the plant.

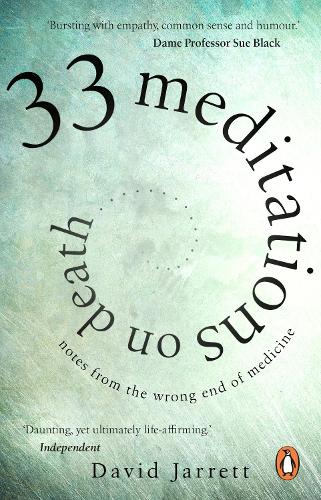

Meanwhile, at the end of each working day, he would go home and sit among his books, reflecting on their death knell, a fate that was in his hands. It was not a good feeling, although their tangible presence for the time being, mollified his growing sense of foreboding. Their strong silence had always shielded him from the vicissitudes of life. Letting go of his cherished library, the kinship and the consolation it brought him, was going to be difficult to say the least. While knowing that one day he would be summoned to join the Great Exodus, Guy had quietly hoped he might be permitted to leave his ancestral collection intact. He was convinced it would serve as an enlightened monument to humanity’s brief residency on Earth, forgetting that in a world without humans all things manmade would eventually be broken down as a new soil is built and a more temperate surface is restored. And books were after all, just another type of human waste.

When the confiscation order finally arrived, Guy had just seven days to pack his books. By then, he had already carefully inspected the half-title and title pages, the endpapers, the chapter divisions and the page margins of every volume for signatures, dedications and marginalia. In Guy’s family, the marking of books had never been forbidden and there were times when he could, through the annotations, feel another reader’s presence. Often it was his grandfather, a prolific commentator who’s witty expressions revealed much about his approbation or otherwise. Ancient household manuals and recipe books overflowed with more feminine tokens of friendship, pressed flowers and pretty postcards. With all the jottings and ephemera scanned and recorded, Guy gently placed the books in the crates and prepared himself for a final farewell to his cherished heirlooms and to his home.

Over the past two centuries the Earth’s temperature had failed to stabilize, despite the many schemes purportedly aimed at avoiding a climate catastrophe. While the most recent, a depopulation programme restricting births to one child per human mother, had been deemed less brutal than some of the alternatives, it was still not enough. Humanity had failed to reverse the damage it had caused. The continuing biodiversity crisis had signalled the beginning of the next mass extinction with the tragic loss of even more species, and it was time for humanity to leave, to give Earth the breathing room it needed.

Regulated mitigation and adaptation had been abandoned in favour of taking the now universally accepted policy of managed retreat to an unprecedented level. Efforts went beyond allocating half the planet to nature, a possible solution suggested over two hundred years earlier, and planning for the ultimate displacement was underway. Replications of the Earth’s biosphere had been established elsewhere in the solar system, in preparation for new settlements.

What mattered now, on Earth, was the legacy of the human race in a post-human future. Greening initiatives were extended, and solid waste infrastructure redesignated to create an industrial scale composting facility known as the Heap. The early signs were encouraging as vast areas that had been ravaged by wildfires were already beginning to regenerate a little faster in the relatively milder temperatures. The compost dressing would help to increase the productivity and resilience of the regenerated soil. It would also improve the environment for what there was of the remaining wildlife, as there was no Noah’s Ark in the Great Exodus, not even for those beloved pets who would no doubt be devoured by their feral cousins. Perhaps the Earth would recover and perhaps one day humans could return, when a less hostile habitat is restored.

Glimpses of new green savannas, tree filled canyons and forests provided solace to those climate refugees who, like Guy, would prefer to stay. On the other hand, he was quietly looking forward to meeting his daughter who had been transported with her mother as a new-born twenty-five years earlier, in accordance with the old drill, women and children first. He relished the prospect of telling her about the family library and, in the sincere belief that words do matter, giving her his secret apologia, a heartfelt written statement addressed to his ancestors who may be keeping tabs on their legacy, and his descendants who, he hoped, would also cherish the sanctity of books. This document, not meant as an admission of guilt or a plea for exoneration, explained in his own words the act of libricide wrought by his own hands.

The deed itself had followed Guy’s usual routine at the Heap, apart from one significant difference. Attesting to his personal loss, he softly uttered this brief committal as he held up each volume in his right hand, before gently lowering it into the treatment bin.

“You have served me well but now you must return to the elements.”

With no particular faith in mind, Guy had wanted to express his gratitude for its enduring gift and acknowledge its sacrifice – trees would hereafter feed on their own kind. He would mourn the loss of his books more than any human, for they were his people, his constant companions who had amplified his understanding and appreciation of the fragile human condition.

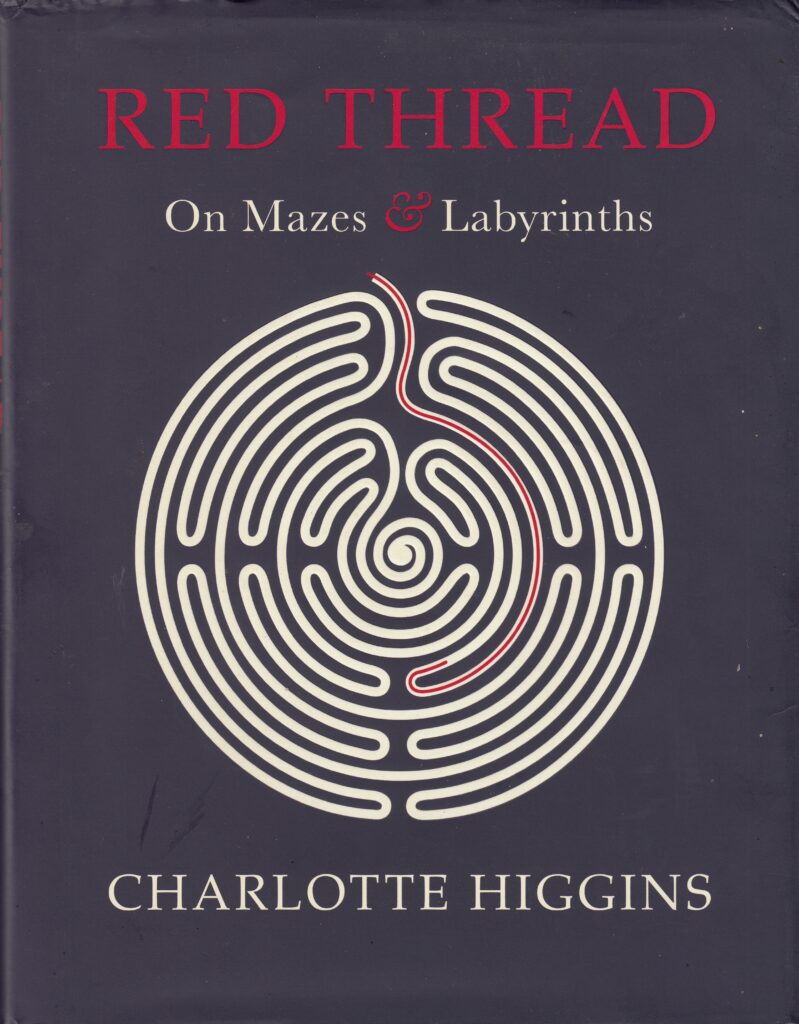

In the circumstances it seemed fitting to dwell upon his treasures that in their own way, foretold this absurd endgame; a first edition of Rachel Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’ heavily annotated by his grandfather who had underscored the reference to Earth’s ‘green mantle’, and a well-thumbed copy of ‘The Uninhabitable Earth: a story of the future’ by David Wallace-Wells, the ‘cautious alarmist’ who had called the space travel solution to climate change a delusion, and anyway, not everyone wanted to live in a spaceship. Guy certainly did not. No solid ground, no trees, plants and flowers, no oceans, lakes and rivers, no skies, no home and, perish the thought, no books. He would especially miss holding those written by his own ancestors, the memoirs and histories that had moderated the influences of the past on their own lives and in turn, on his.

The fateful day arrived, and Guy trudged through the gates of the treatment plant for the last time, his gaze firmly fixed ahead so he would not have to look up at the banner emblazoned with the sickening slogan, ‘THE WORD MADE EARTH’. It seemed a small mercy that his was the final collection to be processed before the completion of the Great Exodus.

When the last book had been dealt with, Guy collected his few belongings and went to board the ultimate solo shuttle to the generation ship, with his illicit mea culpa carefully folded and sewn into the lining of his waistcoat. As he crossed the bridge and stood at the top of the boarding platform, he could not help himself and turned back to take a last look at the panorama of rotting parchment that stretched as far as the eye could see. The discolouring remains of his own pages, gripped in the brittle stiffness of decay, were, he thought, still visible in the fading light, but the sweet odour of sanctity that lingered in the dank air failed to console him. He shuddered and looked down at his hands, indelibly stained lampblack, bearing testimony to the carnage that would forever be etched upon his memory. His brief custody had regrettably been the last chapter in their magnificent lives.

Yet this catastrophe would not define him. The vehemence of his sorrow, while matching the intensity of the love he felt for his lost books, would not render him helpless. The woeful exhaustion brought on by the enforced severance and destruction would pass, and he would soon begin to dream of that library he would one day build for the new humans elsewhere, of the stories he would collect and the shelves he would fill.

Over geologic time, the Earth, no longer shackled by homo sapiens, continued on its tilted way through the seasons towards a green renaissance. The plants and trees, nourished by the new black gold, made it through the searing epoch and began to reclaim their rightful place as the guardians of the climate. Pasqueflowers, imperial purple anemones with bright yellow stamens, bloomed exuberantly across the tundra, much like their hermaphrodite ancestors that had first colonized dry land. Spirited cyclamens, poppies and thistles invaded deserted megacities, and radiant sunflowers played their part in helping to detoxify the contaminated terrain, while strong and resilient rowan trees with their bountiful red threads, heralded a new dawn.

And in this beginning, the soil had remembered those plundered words. The sorry wilderness that Guy had beheld on his departure was now a carpet of diaphanous Madonna lilies dancing in the sunlight, their petals traced with a cipher, markings he would have joyfully recognised.

His beloved books had found their destiny.

Image of Madonna Lily sourced via I, Ranger, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons