Our friend Gwyn recently shared his 2020 reading list on Facebook, having scored each book out of five. He mentioned having received the gift of a Heffers of Cambridge book subscription, a bespoke service whereby the bookshop sends a title to the recipient each month. Over the year, Gwyn read those and many more. Perhaps unsurprisingly, subscription services have become popular during periods of lockdown. It’s interesting to see what others read and I enjoy the various social media posts on people’s favourite books, as well as the book club exchanges. For one year only – 2019 – I compiled monthly collages of the books I read, and in August that year, I wrote a post about my book harvest.

The signing

For Christmas 2020, we were delighted to receive a Box of Stories, from Trevor’s eldest, Ellie, who clearly understands our love of reading. It’s a subscription club and as they say on their website, every time you open a box, you will discover an author or a book you might not have otherwise come across or selected. A percentage of their profits go to charities working for literacy.

I had already read one of the selection, The Rapture by Claire McGlasson, rightly described by The Guardian as a clever fact-based debut about The Panacea Society in Bedford. Trevor and I attended a launch event at the St Neots Library, organised by Jacqui, the manager of Waterstones, St Neots. After Claire’s intriguing talk, I bought a copy of her novel and went over to where she was sitting, in order to get it signed. As I waited to attract her attention, another member of the audience decided to form a queue from the other side. After a minute or so, Claire looked up, saw me, and assumed I was trying to push in front of the (by now) lengthy line of eager fans. She asked if they would mind her signing my copy first, and they said it was fine, lending weight to the false impression that I had not been there first. Such incidents come back to haunt you.

Solace in books

I’ve always found great solace in books and concluded in recent years that reading, rather than counselling, may guide me out of the emotional torture chamber that my mind had become (needless to say, this had not been brought about by the book signing mishap). For many of us, reading is a form of therapy. In her novel, Possession, AS Byatt describes ‘personal’ readings that ‘snatch’ for personal meanings, and I’m drawn to those lines of life that, as she says, describe the indescribable, taking us out of time and towards not blindness but understanding.

The practice of bibliotherapy has a long history, although the term was not coined until 1916, by the North American Unitarian Minister, Samuel McChord Crothers. The author Ann Cleeves, who created the fictional Northumberland detective, Vera Stanhope, once worked for Kirklees Libraries in West Yorkshire, where the Chief Librarian established a bibliotherapy project, attaching three part-time ‘therapists’ to GP practices who prescribed books. Apparently, literature can relieve chronic pain and dementia. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, bibliotherapy is, ‘The use of reading matter for therapeutic purposes in the treatment of nervous disorders.’ I needed to open what the author, Penelope Lively, called that, ‘medicine chest of works.’ I needed to self-medicate.

Although by this time I was using a Kindle, I was not inclined towards an exclusively digital bookish experience and would put the device to one side and employ various ways and means to replenish my supply of solid, hold-in-your-hand-put-on-your-shelf books, with varying degrees of success. Initially, my strategy was aimless; going with the hype, whatever wins the prizes; making a list and playing ‘pin the book’; waiting for a sunny day and grabbing the book on the shelf with a yellow spine, or a sombre day and going for blue; searching the bookshelves of friends in the expectation of a loan that, frankly, would never be returned; picking up books left behind in cafés.

For some months in 2019, I attended a book club in a gastro pub. With each session I grew more exasperated with our club leader who juggled the scoffing and scrolling when searching for reviews on her mobile phone, but it was worth it. As I re-read William Golding’s Lord of the Flies for this club, I was struck by Ralph’s comforting daydream of his bedtime routine at home, where this seemingly civilised boy could reach up and touch his beloved dog-eared books, and for a brief moment, everything was all right.

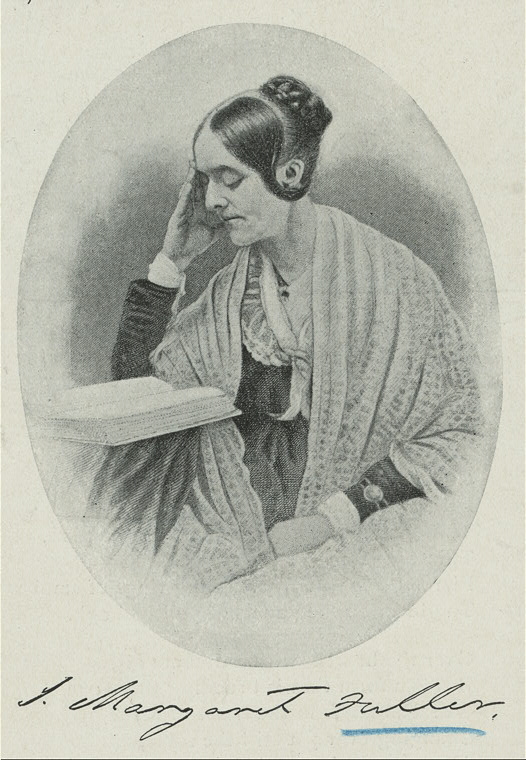

Margaret Fuller Ossoli, North America’s first full-time book reviewer (and the first woman permitted to use Harvard’s library), saw books as, ‘a medium for viewing all humanity’.

Over a century later, in 1968, when the late Lithuanian scholar and human rights activist, Irena Veisaitė, encountered an American bookstore for the first time, she realised how much the Soviet government had stolen from her, by making books so inaccessible in her home country. As she would say, “All of those books and the ideas collected in them belonged to me too!”

Never imagining what it must have been like to have been so deprived, I have always taken my access to books for granted. Reading defined my universe and helped me to grow. The author, Virginia Woolf, who believed that we all learn with feeling, said that after the dust of reading has settled, we must open our minds to a fast flocking of innumerable impressions.

Through reading, I would gain greater insight into the human condition and find a way of unlocking my own emotional truth and through reading, I would learn to accept what I could not change.