Do you have fond memories of brilliant bookshops that have sadly disappeared?

On 9th June 2022, Professor Sam Rayner’s fascinating inaugural UCL lecture, ‘Hidden in the bookshelves: Una Dillon and the ‘formidable’ women booksellers of London, 1930s-1960s’, featured several iconic London establishments, a few of which are still with us, most owned by Waterstones. You can watch her lecture on YouTube.

Growing up In Cambridge, we were spoilt for choice.

William Heffer, William Heffer,

Bowes and Bowes, Bowes and Bowes,

Galloway and Porter, Galloway and Porter,

Deighton Bell, Deighton Bell

This rhyme, sung to the tune of Frère Jacques, harks back to a golden age of bookselling in twentieth-century Cambridge, when the city was served by several excellent establishments, each with its own distinctive history and character.

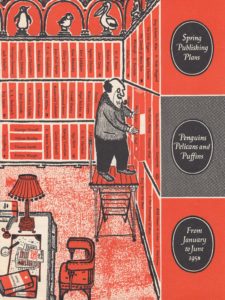

Fifty years ago, our family Saturday morning routine included a visit to the new Heffers Children’s Bookshop, where I would spend all my pocket money on a paperback, often a Puffin or Green Knight imprint at two shillings and sixpence, or from 1971, twenty-five or thirty new pence. Every visit to Heffers was an immersive bookish experience, enhanced by the ambiance of the shop and the people you would find there.

The antiquated shop front of the Children’s Bookshop in those early days disguised the ultra-modern interior, with its turquoise carpet, low sky-blue ceiling, orange staircase lined with mirrors and plastic moulded pea-green tubs for sitting or standing on. Transcended by books in these psychedelic surroundings, seeking my good read for the week, I would now and again glimpse the carnival of stories, and of my mind, all reflected in a large distorting mirror at the top of the stairs.

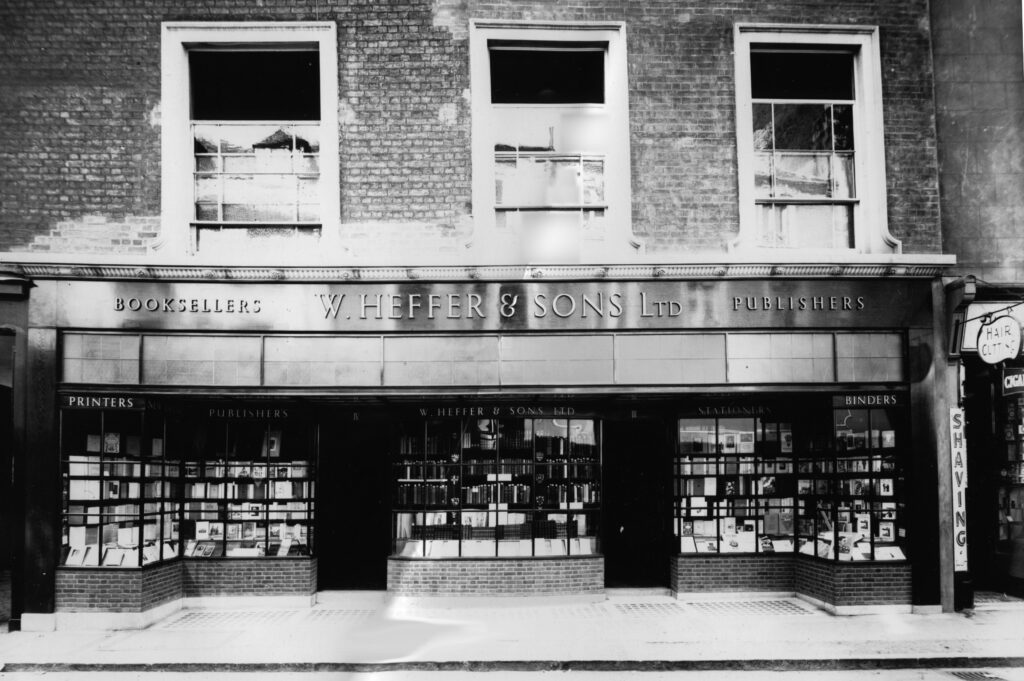

I can also remember the old Heffers bookshop in Petty Cury, with its bottle glass bow windows, polished wooden floors, towering bookshelves, and grand balcony.

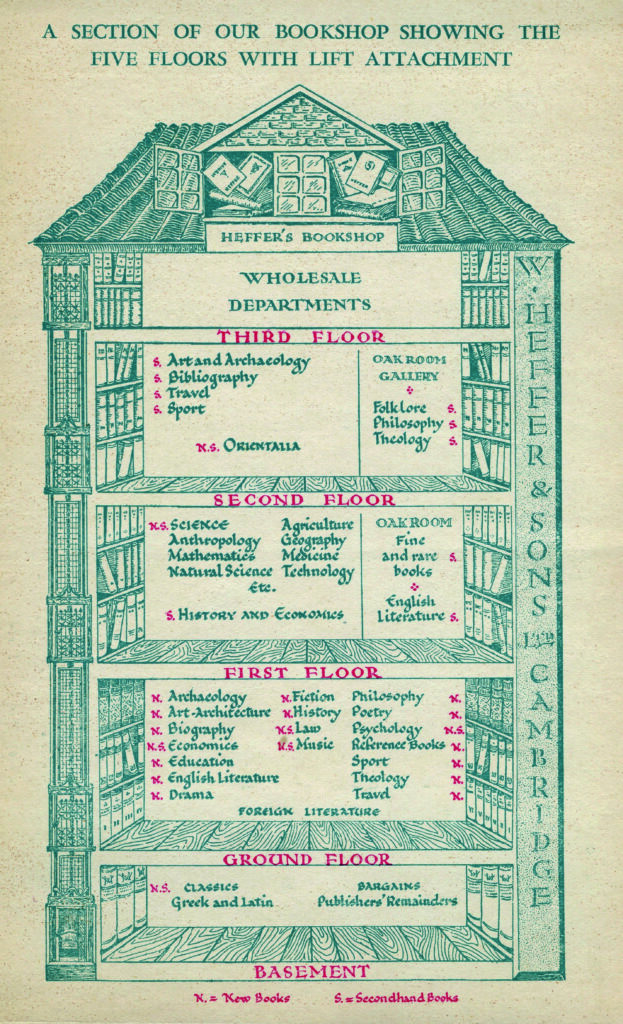

For many years, this iconic bookshop was divided into several departments, all crammed with stock, as described in an early twentieth century brochure,

‘Visitors to this, our Book Shop, constantly remark to us: “How do you find your Books?” “How do you know what you have got?” The questions are not unwarranted, for, though the exterior of the shop is small, the interior – consisting of four floors each 40 feet in depth – is the reverse, and with every available space shelved and crowded with Books: with Books in portentous stacks invading the floors, the questions are very pertinent.’

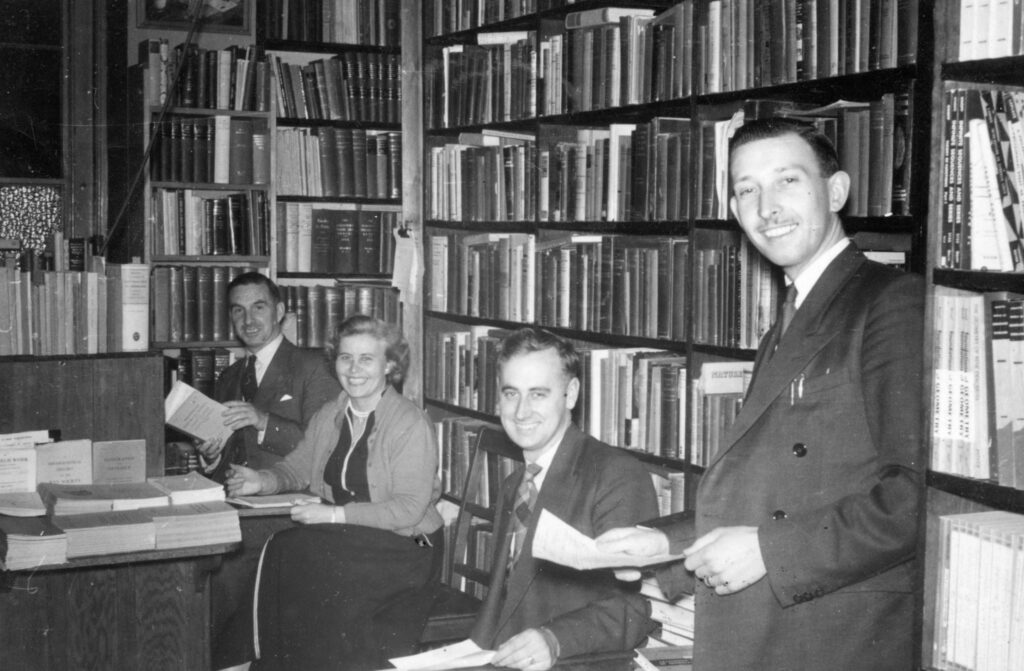

In the 1960s, we would visit my great-auntie Winnie at this bookshop, where she worked as secretary to the renowned bookseller, Mr Frank Stoakley. I would sit patiently on the library steps in the dusky Antiquarian Book Department, inhaling the sweet vanilla and almond aroma of old books, as mother chatted to auntie.

My family clocked up one hundred and twenty years of service for Heffers, starting with great-grandfather Frederick Anstee, employed as an errand boy by William Heffer in 1896, when he opened the Petty Cury shop. Frederick’s two daughters, Lilian (my grandmother) and Winifred (great-auntie Winnie), also worked for the firm. We do not know the exact circumstances in which Frederick was taken on, but in a 1952 biography of his father, William, Sidney Heffer wrote, ‘The increase in the business necessitated employing an errand boy. One lad was anything but a bright specimen–practically uneducated and from a miserable home.’ That lad was Frederick.

William undertook to educate Frederick, insisting he write in a copy book and work out simple sums each night, bringing the results to work the next morning. Frederick thrived by this ‘strange tuition’, and eventually became head of the Science Department at the Petty Cury bookshop.

Amongst great-auntie Winnie’s papers is this portrait of an earnest boy with tight curls, sporting a smart knitted buttoned-up suit, captured at Ralph Starr’s photographic studio in Fitzroy Street, Cambridge. It was taken in 1892 and the boy is Frederick, aged nine years. At the time, his future benefactors were still living above the shop, just a few doors up from the studio. It is likely that the Heffer family arranged and paid for this portrait, as Frederick’s mother, a ‘Barnwell Lady’, would not have had the funds or indeed, the wherewithal, to do so.

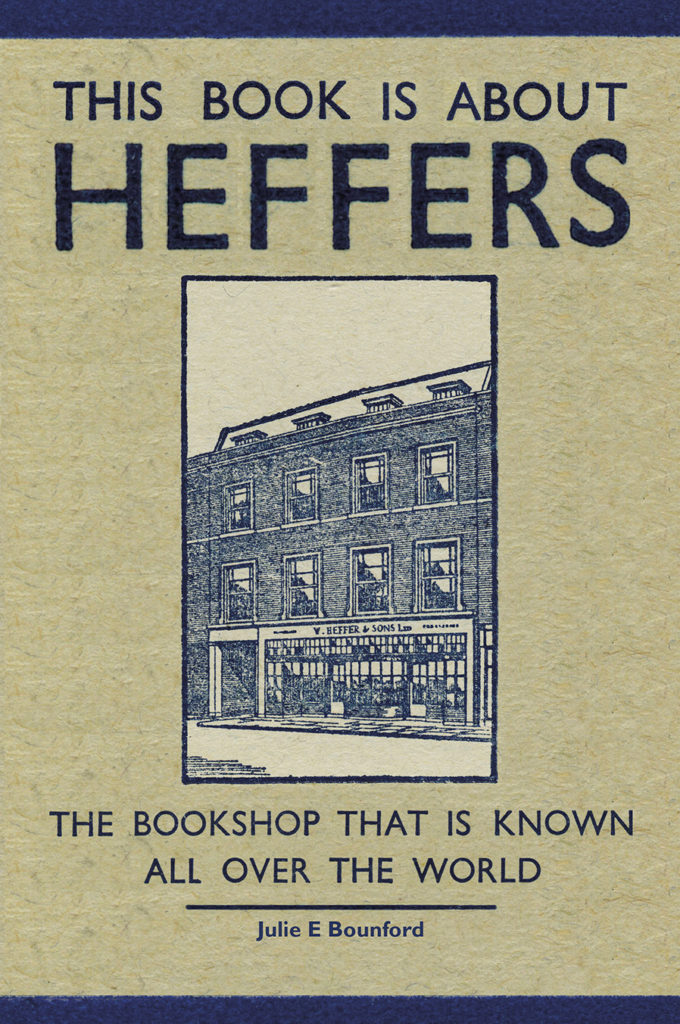

In 2015, I combined my love of the past and of books, by researching and writing a history of Heffers. It was a project close to my heart. There were many quiet moments when I thought about Frederick and the other family members who had worked for the firm. It may sound whimsical, but I sensed their approval of the legacy I was trying to create, and it gave me an inner confidence. It was, and still is, a nice feeling.

’This Book is About Heffers’, won a Cambridgeshire Association for Local History Award, and I’ve given dozens of illustrated talks on the topic to a wide range of groups and societies, and to students. I enjoy meeting people and hearing about their own memories of the firm, so many interesting stories. Sometimes I had repeat visits. An elderly gentleman who had long since retired from Heffers Printers, attended two talks and in tears, expressed his gratitude for my book that had prompted many precious memories. Two ladies who had together attended a Heffers talk, then came to one of my history of mazes talks. My husband, Trevor, went to introduce me to them as they arrived and they exclaimed there was no need, as not only had they already met Julie Bounford, but they had also brought some Heffers memorabilia I might like to keep.

I was especially pleased to meet people who had worked with members of my family. At one talk, a lady took out her album to show me snaps of her Heffers friends and colleagues. Inside was a photograph of her standing with great-auntie Winnie on the balcony at the front of the Sidney Street shop in Cambridge. The Heffers book is dedicated to auntie.

When bookshops close

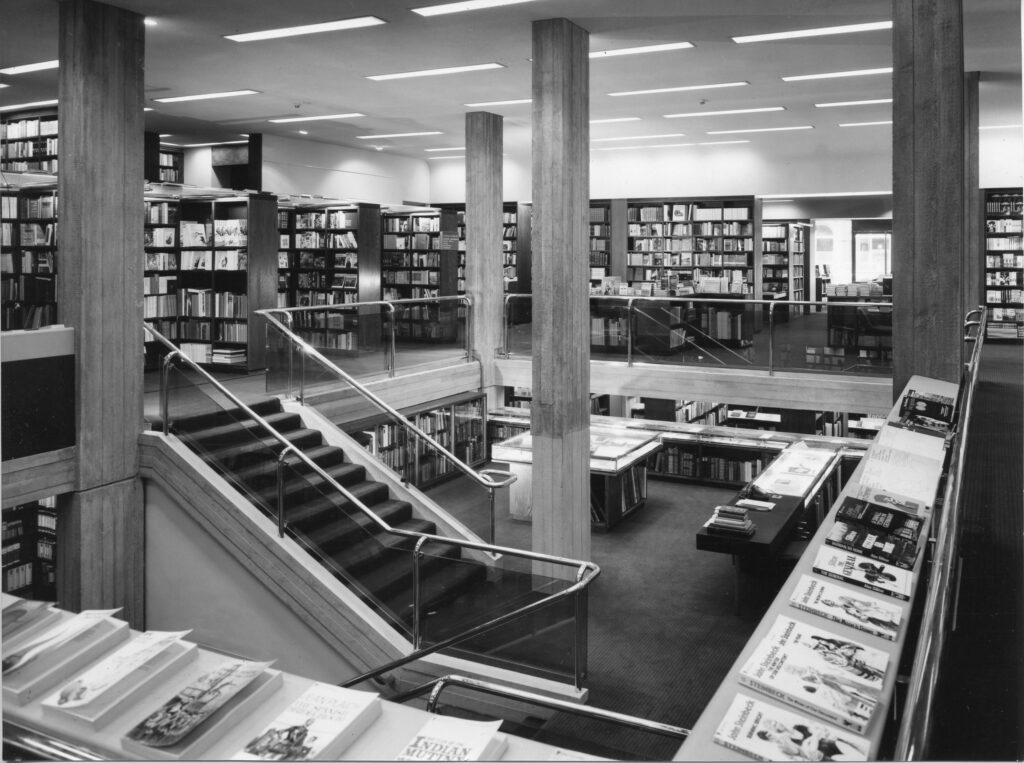

In September 1970, Heffers relocated the Petty Cury bookshop to new premises at 20 Trinity Street, Cambridge, where they remain to this day. While retaining the historic Georgian façade above ground level, the architects designed a wide shopfront in bronze and plate glass for the new premises, providing a, ‘simple and elegant showcase onto the street’, and internally, everything was altered in a radical new concept in bookshop design.

Lord Butler, Master of Trinity College, who officially opened the new bookshop, described the design as ingenious and attractive, combining great spaciousness with a, “superabundance of cosy private nooks where book lovers can tuck themselves away for hours on end perusing their favourite volumes”.

The movement of stock from Petty Cury to Trinity Street was a major operation, carried out by the removal firm Bullens. It took six and a half days, night and day, to transfer more than 80,000 books.

Reuben Heffer, grandson of William and a third generation Heffers director, welcomed the closure of the Petty Cury bookshop, stating at the time that the shop had become almost unworkable, “it was so Dickensian”, he said. But that was what we loved about it.

Despite the generally positive reception amongst staff and customers, the new premises at Trinity Street did not suit everyone. Many employees and customers remember Petty Cury as a more intimate shop. Claire Brown, who had also worked at Blackwell’s in Oxford, was particularly sorry to swap Petty Cury’s polished oak for carpets and chrome,

“It was a great pity that Heffers didn’t adopt the sensible Blackwell’s policy, which was, and is, to keep it looking exactly as it did in the nineteenth century. Heffers, when it left Petty Cury, in the passionate urge to be new and up to date … What Cambridge and Oxford had to sell was the past. The fact that there is a modern business going on is beside the point … They did lose a lot when they left the Petty Cury.”

Opinion was clearly divided and many Cambridge folk still miss that old Dickensian bookshop.

Loss of the Louth charity bookshop

After moving to Louth in Lincolnshire, I took up a volunteering opportunity, as bookselling assistant at the Louth & District Hospice Charity Bookshop. My previous retail experience had been limited and I’ve never been a natural salesman. As a young teenager, I had had a Saturday job at a greengrocer in Akeman Street, Cambridge, standing around in the freezing cold, serving customers and lugging sacks of potatoes for a heavily made-up shop keeper who spent much of the time buffing her nails in the back room. And so, in my application for this role I emphasised instead my love of books and bookshops, and an interest in the history of bookselling informed by my family history.

From February 2022, my regular shift at the Louth bookshop was half a day a week, although, along with some of the other volunteers, from mid-May I helped to cover the manager’s shifts while he volunteered elsewhere on the Polish border, assisting those displaced by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Our volunteer manager was still away when we received news of the bookshop’s imminent closure on 31st May. With just a few days’ notice, we managed to notify many loyal customers, and we held a closing down sale.

Those last few days were distressing for all concerned. Especially those volunteers who had given much of their time over several years to the bookshop and the charity. As a relatively recent contributor, my emotional investment in this enterprise did not compare.

In her inaugural lecture, Sam Raynor declared that Una Dillon did for UCL, what Heffers and Blackwell’s did for Cambridge and Oxford, in establishing a flagship ‘campus’ bookshop. Dillon’s, Heffers, and Blackwell’s (owners of Heffers since 1999), have all been acquired by Waterstones. Of course, our little second-hand charity bookshop in Louth was never going to be of interest to the big W.

I understand what Ernest Heffer (son of William) meant when, in his 1933 address to young booksellers, he declared that a bookshop is a ‘microcosm of everything of importance which is happening in the world’. Although more recently, when I see our world going to hell in a handcart, a bookshop is my means of escape.

As I observed the anguish and chaos in the Louth & District Hospice Charity bookshop on that last day of trading, I felt bereft. It’s true that bookshops are close to the heart of our communities, and long may they remain so.

I never imagined that I would ever take part in closing one down.