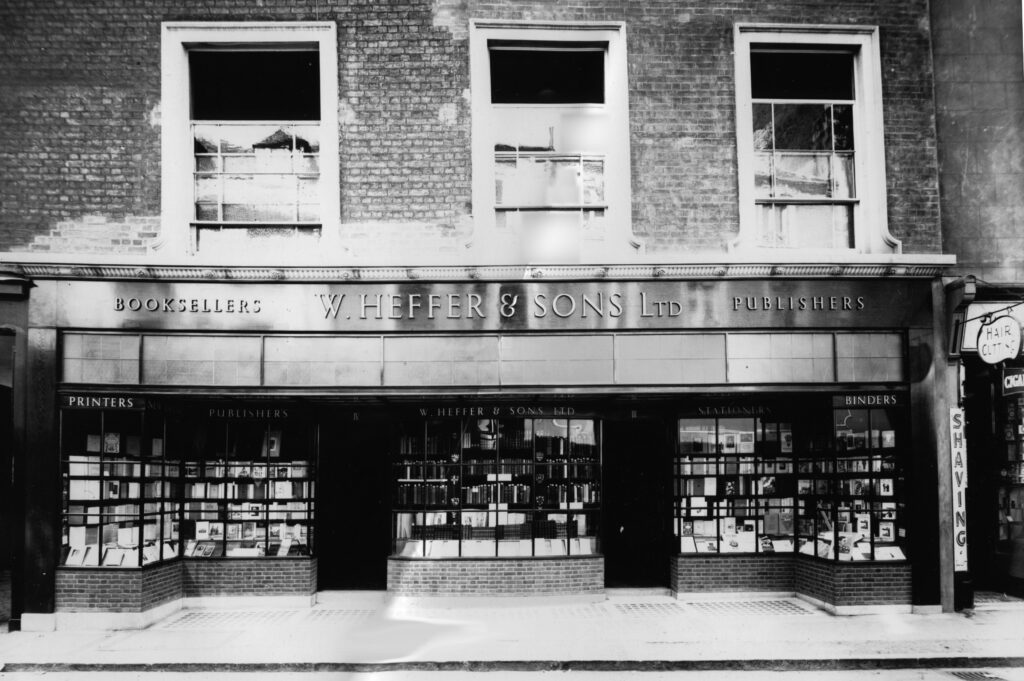

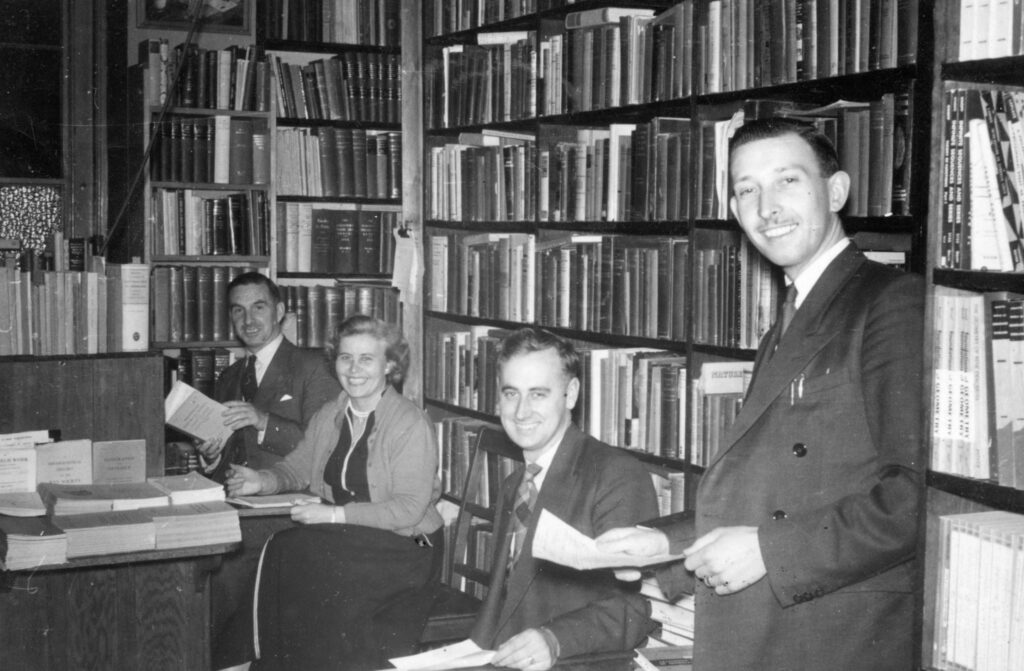

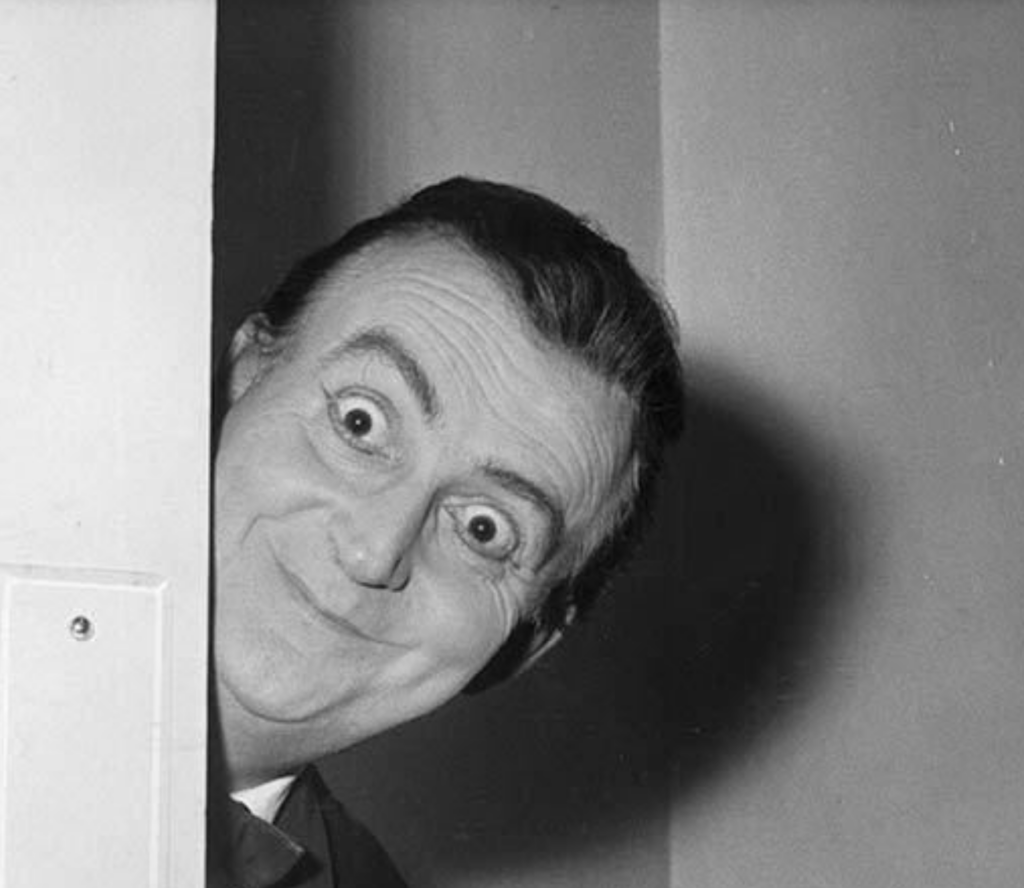

Evelyn Stafford, a dear family friend for all of my 61 years and more, departed this life on 5th July 2022, at the grand age of 95. The above photograph of Eve (4th from the right) with her Heffers of Cambridge colleagues on a 1962 outing to the theatre in London, reveals something of her radiant and fun-loving nature.

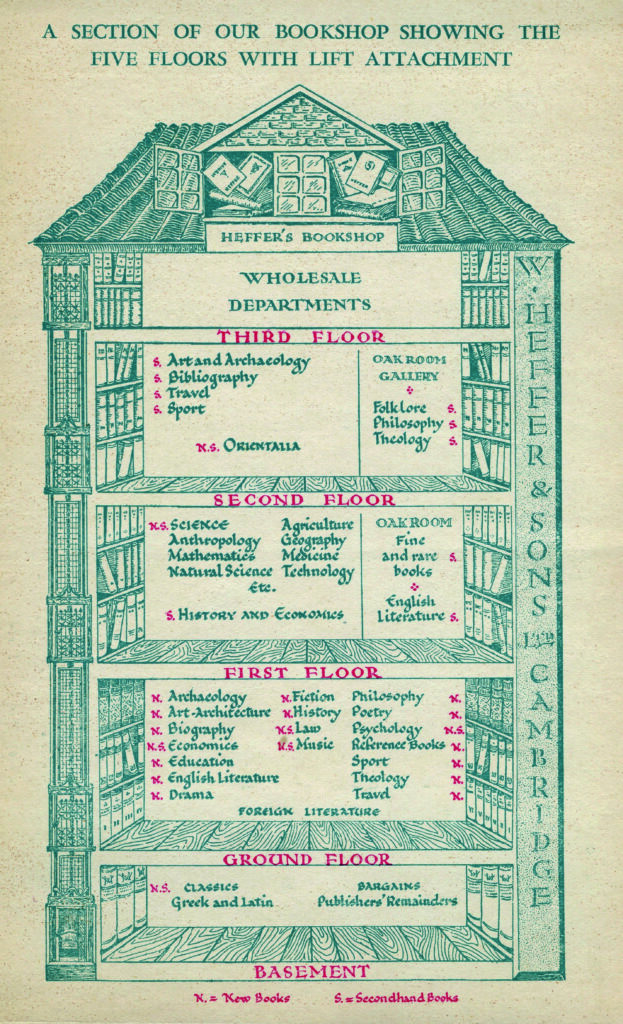

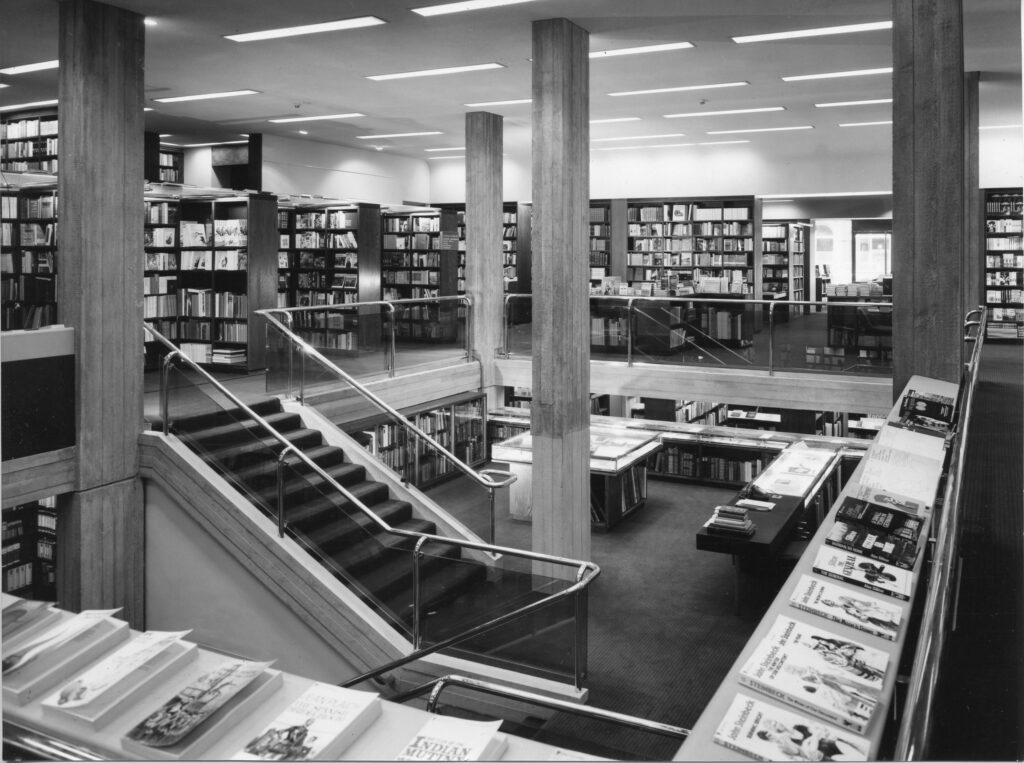

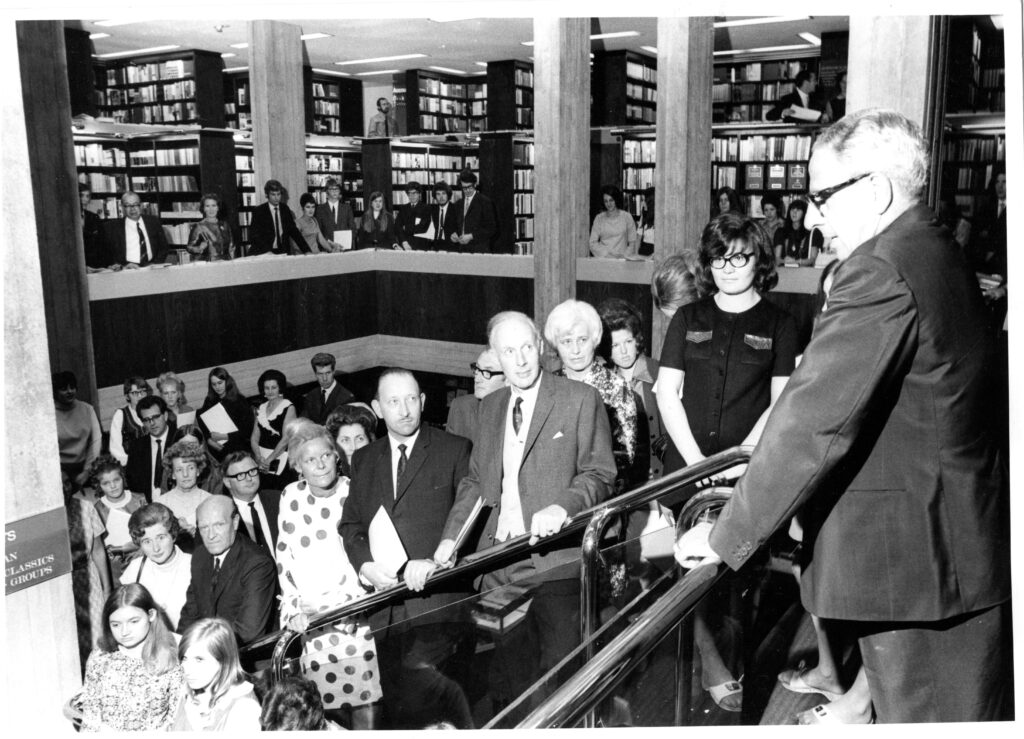

For me, memorable times with Eve include her 90th birthday dinner at Girton College, summer garden parties at King’s College, lunch at the Café Valerie Patisserie in Fitzroy Street, King’s Festival of Nine Lessons & Carols, precious hours together at her home in New Square, recording Eve’s memories of her years working at Heffers, and then at King’s, and fascinating conversations about her spell as a secretary for Lew Grade in London. Several stories ended up in my history of Heffers, published in 2016.

I enjoyed meeting Eve’s former King’s colleagues at the garden parties and was astonished at the end of one gathering to witness her asking the incumbent provost, Professor Michael Proctor, if he would ring for a taxi to take us home. Not only did he oblige, but he also escorted us to the gateway just outside his own residence, so that we would not have far to walk as we waited for our ride. I wondered what my college servant ancestors would have made of that.

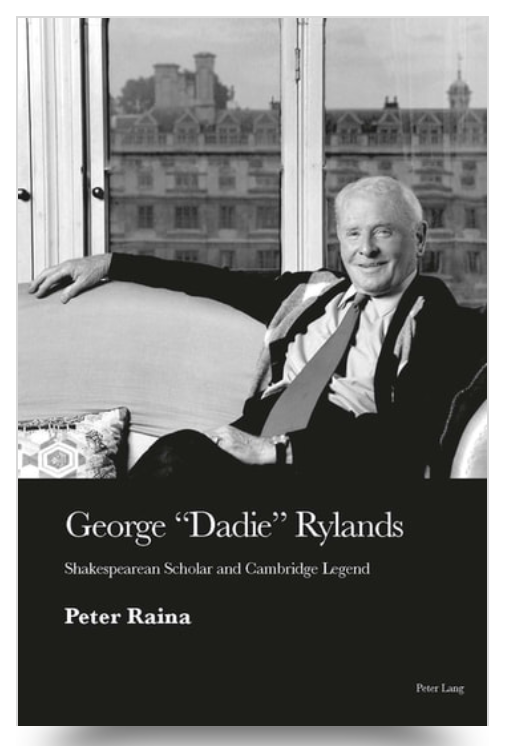

Another King’s garden party ‘host’ was the college dean, the Revd Dr Stephen Cherry, who would kindly share his own stories. Eve especially enjoyed reminiscing with Dr Cherry. An entertaining yarn from the porters involves an ‘ancient man in his nineties’ who got stuck in the bath, as told in Alan James’ memoir, ‘A View from the Lodge’ (2011). The individual in question was said to have been George Humphrey Wolferstan (‘Dadie’) Rylands (1902-1999), Shakespearean scholar and fellow of King’s who, amongst other things, taught the late great Sir Peter Hall to speak in Shakespearean verse.

Eve remembered Dadie and liked to talk about the time he came to her New Square home for afternoon tea. A modest affair compared to the famous sumptuous luncheon hosted in Dadie’s rooms at King’s, portrayed in Virginia Woolf’s, ‘A Room of One’s Own’ (1929), although the sentiment would have been much the same,

‘No need to hurry. No need to sparkle. No need to be anybody but oneself.’

I plan to read Peter Raina’s biography of George “Dadie” Rylands, but will first need to save up. I like to own the biographies I read, especially those with Cambridge connections, and this impressive looking tome is costly.

Defending the honour of college servants

I came across Dadie more directly, when reading his war correspondence in the college archives, from the time he acted as the Domus Bursar during the Second World War, dealing with critical day-to-day matters such as the ‘military occupation’ of college rooms and the resulting tensions. For example, in October 1941, Dadie wrote to Squadron Leader G. Smart about a serious incident,

‘I understand that on Friday the RAF accused my second gardener of stealing potatoes belonging to them, forced him to make a statement and practically put him under arrest. The potatoes were of course his own and were being supplied by him to another of my College servants … It is the most disgraceful incident that has occurred since the Military or RAF took up quarters in College and I must of course report the matter to the Provost and the College Council.’

In his reply, the Squadron Leader explained that just previous to the potato incident, he had found it necessary to send two of his airmen to detention for the theft of a civilian’s child’s cycle, found in exactly the same place as the potatoes.

It will come as no surprise to Cambridge residents that in his acknowledgement Dadie declared,

‘The truth is that in the matter of bicycles Cambridge has no morals and both in war and peace we have unending trouble with undergraduates, servants and everyone else.’

Although he did take great pains to emphasise the particular sensitivities for college servants who had had their bicycle baskets searched by the RAF police, including the Head Butler who is in ‘absolute charge of all the College plate and holds a position of great trust’.

‘What I want to emphasise’ wrote Dadie, ‘is the psychological aspect which is at once dangerous and delicate … It is fatal if the College servants who, it must be remembered, hold a very special position in Colleges after long service – they are on a pension scheme; their families have served the College in the past; it is in a sense their home – I say that it is fatal if they are being to feel that they are being spied upon and suspected, that they can be asked to come to the Guard Room for examination without knowing anything about it. They feel being spoken to by “a policeman” much more than we should – they are often fearfully sensitive about their honesty being impugned and are readier to resent a wrongful charge.’

When I shared this story with Eve, she knew exactly what Dadie had been driving at. There are Cambridge families who have served with great pride for generations and who, even today, feel a strong attachment to ‘their’ college.

I’ve written blog posts on the subject of college servants and have detailed notes totalling 40,000 words from my research at the King’s College archives, plus several hours of interviews that I have yet to transcribe. My explorations were set aside in late 2017, making space for a commission to write ‘The Curious History of Mazes’ (2018) for an American publisher. Since then, my study time has been taken up with paid research contracts and two new consuming interests: firstly, uncovering the truth about my great-great-grandmother, Susan Anstee (1863-1914) whose identity had only recently been revealed, and secondly, exploring the life and times of the romantic author, Norah C. James (1896-1979), whose first novel, ‘Sleeveless Errand’ (1929), made publishing history.

Oooer

As a close friend of my great-auntie Winnie, Eve and their friends Jill and Bet would take it in turn to host a weekly coffee morning. I would occasionally accompany my mother to Winnie’s gatherings at her flat in Nicholson Way, North Arbury, and sometimes to the other ladies’ homes during the 1970s and 80s.

One memorable visit was to Bet’s home on the De Freville Estate, or ‘muesli-belt’ as some liked to call it. As we stood waiting for her to answer the front door, we chatted to her neighbour who told us how much she admired Bet’s “penises”. I couldn’t resist a wry smile when, on a recent visit to our new home in Louth, my brother-in-law Bill who knows about these things, described our gorgeous pink specimens as, “Chelsea standard”.

Eve and friends, along with my family, always enjoyed a social occasion, and her recorded memories are scattered with gently humorous tales of celebrations and outings. For example, at the Heffers staff dances, she would be astounded by her colleagues who would rush to pile up their plates as soon as the buffet was announced, as though they hadn’t eaten for weeks. At one of the dances, not wanting to appear greedy, she and her friend Gill initially took a modest amount and went back for seconds – only to be mortified when someone loudly exclaimed,

“Evelyn and Gillian, don’t be afraid of your big appetites!”

Looking on the bright side

During the pandemic, I had telephone conversations with Eve via the direct line installed in her care home room at Brook House, Cambridge. I had last seen her in person in November 2019, when visiting with my son George, over from Florida for his MSc graduation ceremony in Manchester. George was very fond of ‘auntie’ Eve and would write to her with updates on his adventures in far-flung countries.

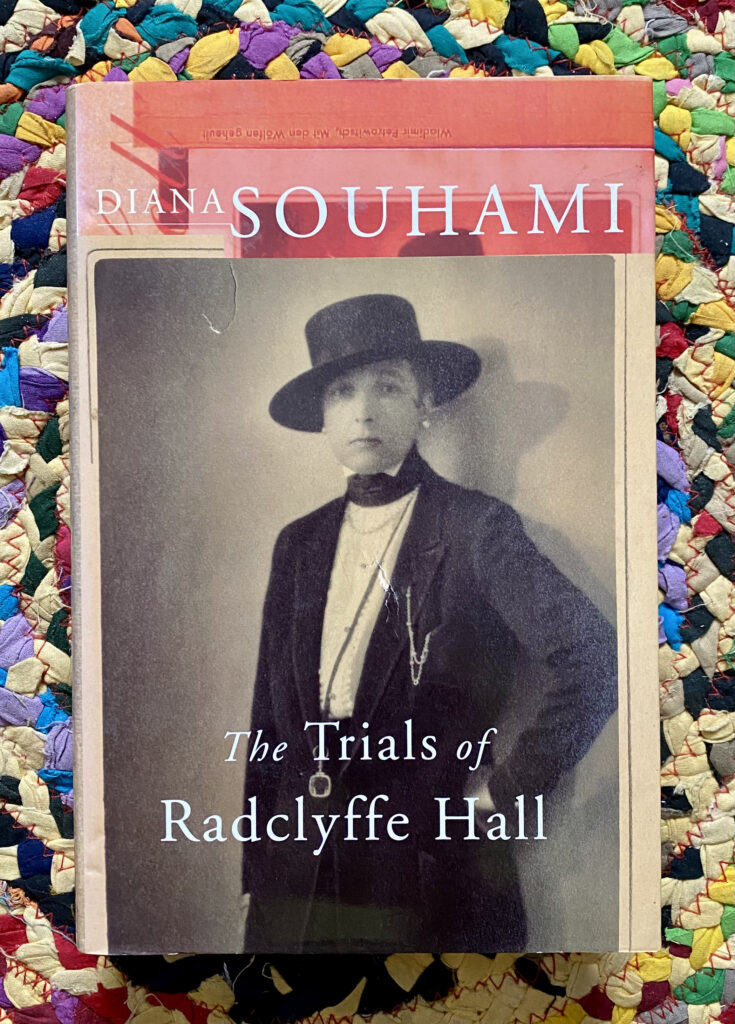

Eve would greet my calls with, “Ah Julie, lovely to hear from you.” We would then chew over world events and our favourite bugbears. Eve was never short of something to say and I would update her on various happenings, our move to Louth, Trevor’s retirement, my contract research, shop work and volunteering, and Heffer related news. I enjoyed telling Eve about my latest book finds and I know she would have been interested in this week’s charity shop treasure, ‘The Trials of Radclyffe Hall’ by Diana Souhami (1998), purchased for £1.00.

Our conversations were upbeat. Even confined to her care home during such precarious times, Eve would count her blessings, and it was no surprise at all to hear ‘What a Wonderful World’ and ‘Always Look on the Bright Side of Life’, being played at her funeral.

She loved us all

When it was time to say goodbye at the end of our calls, Eve would give me her sincerest love. Our contact, while sporadic, was deeply affirming and reassuring.

Eve’s unconditional love for me and my fractious family is testimony to her enduring sensitivity and compassion. She loved us all, and that meant a great deal, particularly in the light of her own personal tragedies, losing her husband Arthur, and her only son, Mervyn.

I have a rather fuzzy memory of Arthur, a jazz pianist who played nightly at The Pagoda Restaurant in Cambridge, although I do remember listening to him play. Arthur died in 1976, aged 58. I don’t remember Mervyn who died suddenly in 1991 in his 42nd year. Eve’s mother, Mrs Farey, who lived at New Square with Eve in her later years until her death in 1985, made a great impression, much like her daughter.

In remembering Eve, I think of Dr Cherry’s words on ‘Lived Bereavement’.

‘When we are recently bereaved, part of what we grieve is that someone else’s life was not always as happy as it might have been. In the period after someone’s death we have an especially acute empathy for what we know of their suffering in life. We wish that they could’ve had a better past, that they could’ve enjoyed an easier, less troubled life … and yet the person they became, the person as whom they died, was not the sum product of the good days and the happy blessings, but the sum of all that happened and all that was drawn from the depths of their character by misfortune and worse. And it is for that person, whose journey we shared, and whom we ultimately admired not for their good fortune but for their triumph over adversity, that we give thanks in death as we should have done more regularly in life.’

I don’t for one moment believe that Eve led a troubled life, but losing Arthur and then Mervyn, her only child, was devastating.

I may not be Christian, or at all religious, but I do have a strong sense of our continuing consciousness, a sense that Eve shared (she would often tell sceptics who denied its existence that they were in for a “nice surprise”), and I like to think that she’s still out there, somewhere.

Sending love your way, dear friend, wherever you may be. X